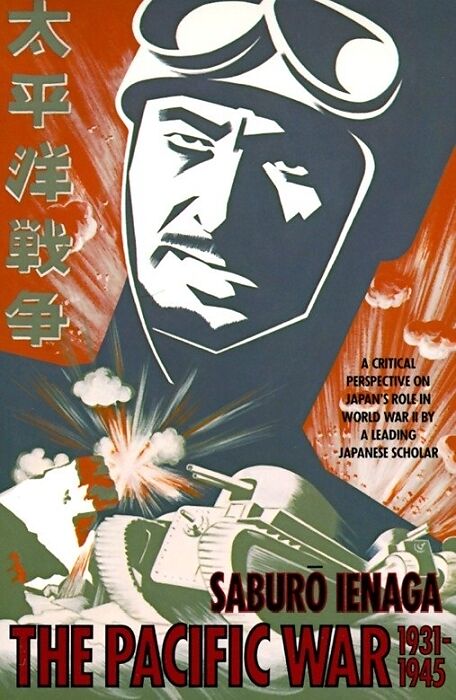

The Pacific War, 1931-1945

Einband:

Kartonierter Einband

EAN:

9780394734965

Autor:

Saburo Ienaga

Herausgeber:

Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

Erscheinungsdatum:

12.07.1979

Zusatztext "A damning indictmentextensively documentedof Japanese imperialism! discrimination! and barbarity overseas." Kirkus Reviews Informationen zum Autor Saburo Ienaga Klappentext A portrayal of how and why Japan waged war from 1931-1945 and what life was like for the Japanese people in a society engaged in total war. 2 Thought Control and Indoctrination Internal Security Laws against Intellectual Freedom In 1868, the new Meiji government moved immediately to control newspapers and publication in order to suppress support for the former regime. A series of internal security laws, starting with the publishing regulation (1869) and the newspaper law (1873), restricted freedom of speech. These laws carried sweeping provisions such as To publish indiscriminate criticism of laws or to slander individuals is prohibited or To add indiscriminately critical comments when describing government actions and laws is forbidden. Officialdom sought immunity from criticism by these regulations. The 1875 libel law and newspaper regulations were extremely severe; there was for a time a reign of terror against journalists. A vigorous nationwide challenge to the new government, the People's Rights movement, occurred in the 1870s and 1880s. To divide and weaken the movement, authorities dangled the carrot of financial rewards before some of the opposition. Others were harassed, locked up, and silenced. Strict enforcement of ever-tougher internal security laws proved to be the most effective weapon against dissent: regulations on assembly (1880), revision and amendment of the same law in 1882, revision of the newspaper regulation (1883), and a law prohibiting the disclosure of petitions to the throne and the government (1884). Freedom of assembly and association were also severely restricted. The People's Rights movement was destroyed, and political activity of any kind became extremely difficult. But the People's Rights activists did achieve their immediate objective: the establishment of an elected parliament. The government announced in late 1881 that a constitution providing for an elected assembly would be drafted by 1890. The dissidents had demanded that the new constitution include guaranteed political rights. Draft constitutions prepared by the left wing of the Jiyuto (Liberal party) contained absolute guarantees of intellectual freedom, academic and educational, and of speech. The People's Rights movement was a bid for a national assembly, a sharing of governmental power, and simultaneously a struggle to establish freedom of expression and basic human rights. Its failure aborted the drive for freedom of speech. After crushing the movement, the government secretly and arbitrarily drafted the constitution and promulgated it on February 11, 1889. There was no popular participation in the process; the emperor presented it to the people as an imperial gift. The Meiji Constitution did not guarantee basic human rights. Freedom expression was recognized only within the limits of the law. The liberties granted in the constitution could be virtually abolished by subsequent laws. Restrictions soon tumbled from the government's authoritarian cornucopia. Freedom of publication was affected by the Publication Law (1893) and the Newspaper Law (1909); freedom of assembly and association by the Assembly and Political Organizational Law (1890) and its successor, the Public Order Police Law of 1900; and intellectual freedom by the lèse majesté provision of the criminal code and by the Peace Preservation Law (1925). Movies and theatrical performances were strictly controlled by administrative rulings rather than by laws passed by the Diet. Thought and expression were so circumscribed that only a small sphere of freedom remained. The internal security laws were primarily intended to prevent discussion or ...

"A damning indictment—extensively documented—of Japanese imperialism, discrimination, and barbarity overseas." —Kirkus Reviews

Autorentext

Saburo Ienaga

Klappentext

A portrayal of how and why Japan waged war from 1931-1945 and what life was like for the Japanese people in a society engaged in total war.

Leseprobe

2

Thought Control and Indoctrination

Internal Security Laws against Intellectual Freedom

In 1868, the new Meiji government moved immediately to control newspapers and publication in order to suppress support for the former regime. A series of internal security laws, starting with the publishing regulation (1869) and the newspaper law (1873), restricted freedom of speech. These laws carried sweeping provisions such as “To publish indiscriminate criticism of laws or to slander individuals is prohibited” or “To add indiscriminately critical comments when describing government actions and laws is forbidden.” Officialdom sought immunity from criticism by these regulations. The 1875 libel law and newspaper regulations were extremely severe; there was for a time a reign of terror against journalists.

A vigorous nationwide challenge to the new government, the People’s Rights movement, occurred in the 1870s and 1880s. To divide and weaken the movement, authorities dangled the carrot of financial rewards before some of the opposition. Others were harassed, locked up, and silenced. Strict enforcement of ever-tougher internal security laws proved to be the most effective weapon against dissent: regulations on assembly (1880), revision and amendment of the same law in 1882, revision of the newspaper regulation (1883), and a law prohibiting the disclosure of petitions to the throne and the government (1884). Freedom of assembly and association were also severely restricted. The People’s Rights movement was destroyed, and political activity of any kind became extremely difficult.

But the People’s Rights activists did achieve their immediate objective: the establishment of an elected parliament. The government announced in late 1881 that a constitution providing for an elected assembly would be drafted by 1890. The dissidents had demanded that the new constitution include guaranteed political rights. Draft constitutions prepared by the left wing of the Jiyūtō (Liberal party) contained absolute guarantees of intellectual freedom, academic and educational, and of speech. The People’s Rights movement was a bid for a national assembly, a sharing of governmental power, and simultaneously a struggle to establish freedom of expression and basic human rights. Its failure aborted the drive for freedom of speech. After crushing the movement, the government secretly and arbitrarily drafted the constitution and promulgated it on February 11, 1889. There was no popular participation in the process; the emperor presented it to the people as an “imperial gift.”

The Meiji Constitution did not guarantee basic human rights. Freedom expression was recognized only “within the limits of the law.” The liberties granted in the constitution could be virtually abolished by subsequent laws. Restrictions soon tumbled from the government’s authoritarian cornucopia. Freedom of publication was affected by the Publication Law (1893) and the Newspaper Law (1909); freedom of assembly and association by the Assembly and Political Organizational Law (1890) and its successor, the Public Order Police Law of 1900; and intellectual freedom by the lèse majesté provision of the criminal code and by the Peace Preservation Law (1925). Movies and theatrical performances were strictly controlled by administrative rulings rather than by laws passed by the Diet. Thought and expression were so circumscribed that only a small sphere of freedom remained.

The internal security laws were …

Leider konnten wir für diesen Artikel keine Preise ermitteln ...

billigbuch.ch sucht jetzt für Sie die besten Angebote ...

Die aktuellen Verkaufspreise von 6 Onlineshops werden in Realtime abgefragt.

Sie können das gewünschte Produkt anschliessend direkt beim Anbieter Ihrer Wahl bestellen.

Loading...

Die aktuellen Verkaufspreise von 6 Onlineshops werden in Realtime abgefragt.

Sie können das gewünschte Produkt anschliessend direkt beim Anbieter Ihrer Wahl bestellen.

| # | Onlineshop | Preis CHF | Versand CHF | Total CHF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Seller | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |